|

|

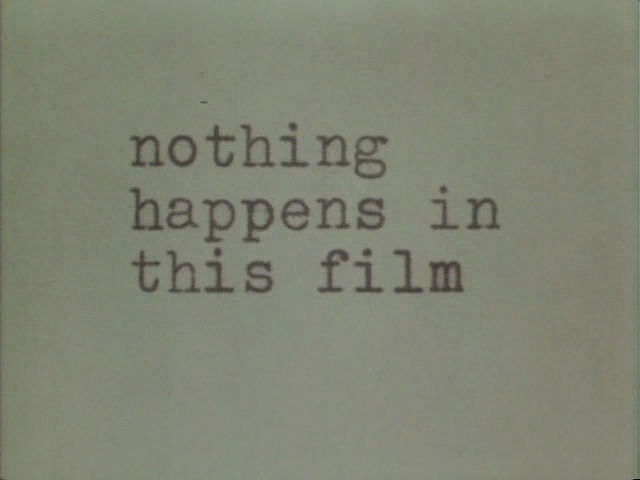

Prin 2010 concluzionam că nu găsesc nimic mai plictisitor decât un apus de soare. Se pare că m-am pripit. Etapizarea rutinei este mai plictisitoare (o plictiseală „în stat”). Ca la sfârșitul calendarului să produci ceva, îți trebuie, firește, o rutină ceva mai sofisticată, care trece de spălatul pe față. Uneori mai trecem și peste ăla, în semn de diversificare. Cineva a crezut că, arhivând procedurile de organizare a cotidianului, va putea construi un ghid (folositor) de dez-rutinare, sau măcar de particularizare a acestui spectacol de circ disciplinat, interval de timp care-și spune zi (sic). În linia credinței populare și a diferenței dintre plictiseala productivă și neproductivă, dacă mă plictisesc în același fel în care se plictisește X (care a ajuns unde a ajuns), o s-o pățesc și eu la fel. Și mai e ceva: interesul axiomatic (lol) față de rutina matinală. Cum (sau chiar prin ce mișcări) începe ziua unui om care se plictisește? Aici e punctum-ul și intriga nimicului care învârte și uniformizează, prin rotire repetată, un ceva. De pe Daily Routines (blog transformat în carte – vezi aici) am extras, să le spun, niște liste de cumpărături (la cele mai bune prețuri de pe piață). Dar amăgire stop: cine a fost cinstit, a recunoscut că a ajuns unde a ajuns datorită norocului (enunț, din nou, axiomatic, lol). Napoleon, amintește omul cinstit, ordona să i se aducă generali care au noroc, nu cine-știe-ce generali cu tărâțe (creiere, pentru…) strategice și militare, mie îmi trebuie generali care au noroc; în felul ăsta gândea (cu mare tact) Napoleon. Cuvântul-cheie e serendipity, de altfel inclus în lista celor mai dificile zece cuvinte de tradus. După ce întoarceți brazda serendipity cu susul în jos, ca să vedeți ce e dedesubt, o să vă liniștiți. O să fie bine pe seară. Prin 2010 concluzionam că nu găsesc nimic mai plictisitor decât un apus de soare. Se pare că m-am pripit. Etapizarea rutinei este mai plictisitoare (o plictiseală „în stat”). Ca la sfârșitul calendarului să produci ceva, îți trebuie, firește, o rutină ceva mai sofisticată, care trece de spălatul pe față. Uneori mai trecem și peste ăla, în semn de diversificare. Cineva a crezut că, arhivând procedurile de organizare a cotidianului, va putea construi un ghid (folositor) de dez-rutinare, sau măcar de particularizare a acestui spectacol de circ disciplinat, interval de timp care-și spune zi (sic). În linia credinței populare și a diferenței dintre plictiseala productivă și neproductivă, dacă mă plictisesc în același fel în care se plictisește X (care a ajuns unde a ajuns), o s-o pățesc și eu la fel. Și mai e ceva: interesul axiomatic (lol) față de rutina matinală. Cum (sau chiar prin ce mișcări) începe ziua unui om care se plictisește? Aici e punctum-ul și intriga nimicului care învârte și uniformizează, prin rotire repetată, un ceva. De pe Daily Routines (blog transformat în carte – vezi aici) am extras, să le spun, niște liste de cumpărături (la cele mai bune prețuri de pe piață). Dar amăgire stop: cine a fost cinstit, a recunoscut că a ajuns unde a ajuns datorită norocului (enunț, din nou, axiomatic, lol). Napoleon, amintește omul cinstit, ordona să i se aducă generali care au noroc, nu cine-știe-ce generali cu tărâțe (creiere, pentru…) strategice și militare, mie îmi trebuie generali care au noroc; în felul ăsta gândea (cu mare tact) Napoleon. Cuvântul-cheie e serendipity, de altfel inclus în lista celor mai dificile zece cuvinte de tradus. După ce întoarceți brazda serendipity cu susul în jos, ca să vedeți ce e dedesubt, o să vă liniștiți. O să fie bine pe seară.

Paul Auster:

The usual. I got up in the morning. I read the paper. I drank a pot of tea. And then I went over to the little apartment I have in the neighborhood and worked for about six hours. After that, I had to do some business. My mother died two years ago, and there was one last thing to take care of concerning her estate—a kind of insurance bond I had to sign off on. So, I went to a notary public to have the papers stamped, then mailed them to the lawyer. I came back home. I read my daughter’s final report card. And then I went upstairs and paid a lot of bills. A typical day, I suppose. A mix of working on the book and dealing with a lot of boring, practical stuff. [Mai mult]

Will Self:

Rituals. Smoking–pipes, cigars, special brands, accessories, the whole bollocks. Coffee, tea, strange infusions–I have a stove on my desk. Fetishising typewriters, pens, etc. Overall, though, I have a healthy appetite for solitude. If you don’t, you have no business being a writer. [Mai mult]

Gustave Flaubert:

Days were as unvaried as the notes of the cuckoo. Flaubert, a man of nocturnal habits, usually awoke at 10 a.m. and announced the event with his bell cord. Only then did people dare speak above a whisper. His valet, Narcisse, straightaway brought him water, filled his pipe, drew the curtains, and delivered the morning mail. Conversation with Mother, which took place in clouds of tobacco smoke particularly noxious to the migraine sufferer, preceded a very hot bath and a long, careful toilette involving the regular application of a tonic reputed to arrest hair loss. At 11 a.m. he entered the dining room, where Mme Flaubert; Liline; her English governess, Isabel Hutton; and very often Uncle Parain would have gathered. Unable to work well on a full stomach, he ate lightly, or what passed for such in the Flaubert household, meaning that his first meal consisted of eggs, vegetables, cheese or fruit, and a cup of cold chocolate. The family then lounged on the terrace, unless foul weather kept them indoors, or climbed a steep path through woods behind their espaliered kitchen garden to a glade dubbed La Mercure after the statue of Mercury that once stood there. Shaded by chestnut trees, near their hillside orchard, they would argue, joke, gossip, and watch vessels sail up and down the river. Another site of open-air refreshment was the eighteenth-century pavilion. After dinner, which generally lasted from seven to nine, dusk often found them there, looking out at moonlight flecking the water and fisherman casting their hoop nets for eel. [Mai mult]

Franz Kafka:

Begley is particularly astute on the bizarre organization of Kafka’s writing day. At the Assicurazioni Generali, Kafka despaired of his twelve-hour shifts that left no time for writing; two years later, promoted to the position of chief clerk at the Workers’ Accident Insurance Institute, he was now on the one-shift system, 8:30 AM until 2:30 PM. And then what? Lunch until 3:30, then sleep until 7:30, then exercises, then a family dinner. After which he started work around 11 PM (as Begley points out, the letter- and diary-writing took up at least an hour a day, and more usually two), and then “depending on my strength, inclination, and luck, until one, two, or three o’clock, once even till six in the morning.” Then “every imaginable effort to go to sleep,” as he fitfully rested before leaving to go to the office once more. This routine left him permanently on the verge of collapse. [Mai mult]

J. M. Coetzee:

“Coetzee,” says the writer Rian Malan, “is a man of almost monkish self-discipline and dedication. He does not drink, smoke or eat meat. He cycles vast distances to keep fit and spends at least an hour at his writing-desk each morning, seven days a week.” [Mai mult]

Immanuel Kant:

[…] After getting up, Kant would drink one or two cups of tea — weak tea. With that, he smoked a pipe of tobacco. The time he needed for smoking it “was devoted to meditation.” Apparently, Kant had formulated the maxim for himself that he would smoke only one pipe, but it is reported that the bowls of his pipes increased considerably in size as the years went on. He then prepared his lectures and worked on his books until 7:00. His lectures began at 7:00, and they would last until 11:00. With the lectures finished, he worked again on his writings until lunch. Go out to lunch, take a walk, and spend the rest of the afternoon with his friend Green. After going home, he would do some more light work and read. [Mai mult]

Karl Marx:

His mode of living consisted of daily visits to the British Museum reading-room, where he normally remained from nine in the morning until it closed at seven; this was followed by long hours of work at night, accompanied by ceaseless smoking, which from a luxury had become an indispensable anodyne [Mai mult]

Philip Roth:

When I came to visit, it was a late-winter morning, and the snow was piled high around the studio. Roth was wearing a blue Shetland sweater, green corduroy pants. Often there is tweed. He dresses like a graduate student of the late fifties. He led me to the back room. There was a team photograph of the 1947 Brooklyn Dodgers. There were free weights, a lifting bench, and an exercise mat. He had quintuple-bypass surgery eleven years ago and is determined to keep in shape. He stays out here all day and into the evening: no telephone, no fax. Nothing gets in. In the late afternoons, he takes long walks, often trying to figure out connections and solve problems in the novel that’s possessing him.

“I live alone, there’s no one else to be responsible for or to, or to spend time with,” Roth said. “My schedule is absolutely my own. Usually, I write all day, but if I want to go back to the studio in the evening, after dinner, I don’t have to sit in the living room because someone else has been alone all day. I don’t have to sit there and be entertaining or amusing. I go back out and I work for two or three more hours. If I wake up at two in the morning–this happens rarely, but it sometimes happens–and something has dawned on me, I turn the light on and I write in the bedroom. I have these little yellow things all over the place. I read till all hours if I want to. If I get up at five and I can’t sleep and I want to work, I go out and I go to work. [Mai mult]

Joyce Carol Oates:

I try to write in the morning very intensely, from 8:30 to 1 p.m. When I’m traveling, I can work from 10 p.m. to 3 a.m. Alone, I don’t sleep that well. I get a lot of work done in hotel rooms. The one solace for loneliness is work. I hand write and then I type. I don’t have a word processor. I write slowly. [Mai mult]

Comentarii comentarii

Tags: apus, daily routines, etapizare, flaubert, kant, napoleon, paul auster, proceduri, roth, rutina, serendipity Scroll to top

|