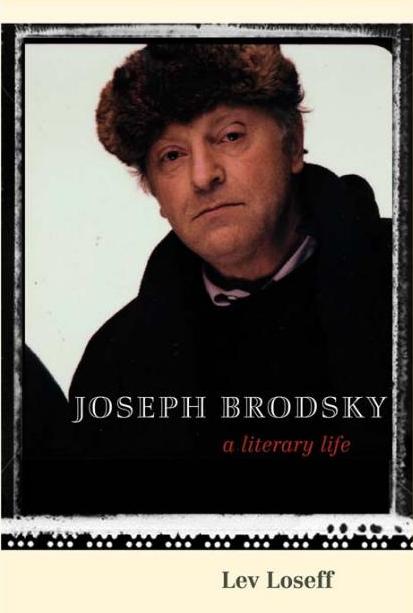

Joseph Brodsky x Lev Loseff

|

———— Extract from Joseph Brodsky: A Literary Life Joseph Brodsky was a close friend of mine for more than thirty years, and I am fairly certain that he would not have been enthusiastic about anyone “writing his life.” Most likely, he would have shrugged and said, “Well, if you feel like doing it… ,” then switched the conversation to something he thought more interesting. But Brodsky’s attitude toward writers’ biographies was fraught with contradictions. He always insisted on the irrelevance of his life to his poetry, but he was an avid reader of other poets’ lives. For example, in his Nobel lecture he said: “It is precisely their lives [Mandelstam’s, Akhmatova’s, Tsvetaeva’s, Auden’s, and Frost’s], no matter how tragic or bitter they were, that often moves me—more often perhaps than the case should be—to regret the passage of time.” From the beginning I set out to write a literary biography, not a chronicle of Brodsky’s life. Being a good friend of one’s subject is not necessarily an advantage: here one must strive for objectivity. But I cannot comment on Joseph’s life and work dispassionately, not only because I loved him but also because I thought him a genius. “Genius” is not a scholarly term. Its common use is mainly emotive: “You’re a genius!” For me, “genius” is first and foremost a cognate of “genetic.” A one-in-a-million genetic makeup creates a person of unusual creative potential, willpower, and charisma. It may offend our democratic sensibilities to admit that such rare birds are so different from the rest of our common flock, but in fact they are. Marina Tsvetaeva, who was one of that rare breed herself, wrote: “Genius: being in the highest degree susceptible to inspiration first, and, second, being in command of this inspiration. The highest degree of mental disintegration, and—the highest ability to collect oneself. The highest degree of passivity and the highest degree of activity. It is letting oneself be destroyed down to some last atom, and then to re-create the world out of that atom’s survival (resistance).” To a Christian, Tsvetaeva’s ecstatic definition of genius must sound almost sacrilegious. “Letting oneself be destroyed down to some last atom, and then to re-create the world”—is she not trying to equate her poet-genius with the Saviour? Or we can recall Pushkin’s oft-quoted words: “The mob devours confessions, memoirs, etc., because in its baseness it relishes the humiliation of the supreme, the weakness of the powerful. Upon discovering any unsavory detail, it is delighted: He is despicable, just like us; revolting, just like us! That’s a damn lie, bastards: even when despicable and revolting, he is not like you—he is different.” These voices from the past confirmed my own intuition: it is impossible for me or anyone I know to lay claim to a total understanding of Brodsky, the man and the poet. A critic may successfully comment on some aspects of his poetry and a writer may well describe some event in his life, but there will be always something equally important left out—something inexplicable, indescribable, unfathomable. The lesser cannot comment upon the greater. This last phrase I’ve borrowed from Brodsky. Once, when invited to give a talk about the nature of artistic creativity, he started by expressing doubt that the phenomenon could be explained at all. To explain why artists create is as impossible as explaining why cats meow (hence the title of his essay “A Cat’s Meow”), and he added: “The lesser commenting upon the greater has, of course, a certain humbling appeal, and at our end of the galaxy we are quite accustomed to this sort of procedure.” I engaged in “this sort of procedure” when a Russian publisher commissioned me to prepare an annotated edition of Brodsky’s poetry. That project implied a long, slow rereading of the texts and promised immense pleasure. I am an avid reader of good commentaries myself. Unlike interpretive analyses, which more often than not are glass-bead games or fulfillment of tenure-track requirements, a genuine commentary enhances the pleasure and the understanding of the text. Moreover, it serves a public purpose. I like the apt, albeit ingenuous, title that the eighteenth-century poet Gavrila Derzhavin gave to his commentaries on his own works: “Annotations to works as regards obscure passages within them, proper names, circumlocutions and ambiguous utterances, the true meaning whereof is known to the author alone.” This is exactly the sort of commentary I wrote on approximately five hundred collected and uncollected poems by Brodsky. The time will come when someone will write a proper biography of Brodsky, wherein his life will be presented in much greater detail. The future biographer will undoubtedly make use of those of his personal papers that are currently closed to public scrutiny. Moreover, the future biographer will not be hindered by any obligation to protect the privacy of those who were intimately related to the poet at different periods in his life. This book is merely an attempt at re-creating the “noise of time,” as Mandelstam called it—that is, the heterogeneous cultural background of the poet’s life and work: the books he read cover to cover and the books he just skimmed; the words of people dear to him and the voices of the street; world events and personal troubles; travels, buildings, paintings, music, meals, wines, jobs, diagnoses, and so on and so forth. It does not aspire to be a biography of the poet, although it begins: “Iosif Aleksandrovich Brodsky was born on May 24, 1940, in Leningrad…” Cartea poate fi comandată de aici. Comentarii |